Whether deemed a “must have,” as some contestants on The Fashion Show insisted, or a hideous mistake, the so-called harem pant is back in a big, billowy way. But the resurgence of the harem pant in the long shadow of war in the Middle East –specifically, those conflicts being pursued by the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan– should prompt a raised eyebrow for more than its unconventional shape.*

Whether deemed a “must have,” as some contestants on The Fashion Show insisted, or a hideous mistake, the so-called harem pant is back in a big, billowy way. But the resurgence of the harem pant in the long shadow of war in the Middle East –specifically, those conflicts being pursued by the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan– should prompt a raised eyebrow for more than its unconventional shape.*

While I enjoy the intellectual and artistic transformation of the shape of the body through clothing (see Issey Miyake’s Pleats, Please!), I also find it useful to be skeptical of the ways that geopolitical rubrics of race, nation, gender and sexuality are mapped through such transformations (think bullshit Orientalisms perpetrated by hostile fashion journalists about the so-called “Hiroshima bag lady” of 1980s Japanese designers). The most obvious yet often unasked question –why the term harem to qualify this pant?– requires a history lesson.

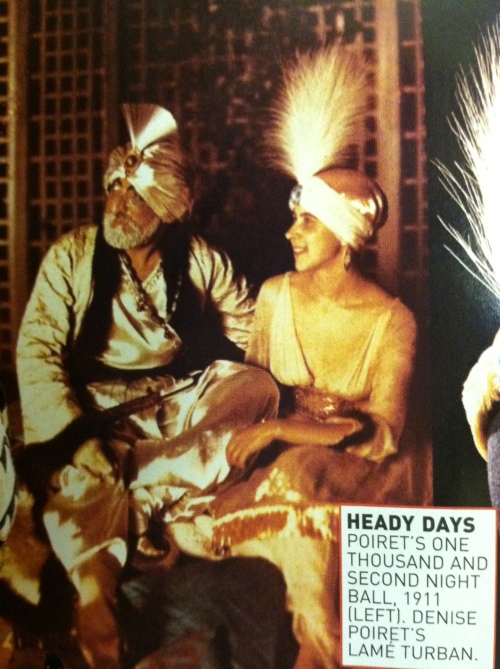

At the turn of the 20th century, Western imperial forces were busily carving up the rest of the world into territories, colonies, and protectorates. In between the 1880s and the First World War, the “race for Africa” and Western Asia proliferated claims among the European powers for political influence and direct rule in Egypt, Turkey, Persia (now known as Iran), and Morocco. In 1911, the same year that Morocco was named a protectorate of France, famed Parisian fashion designer Paul Poiret “introduced” the harem pant to avant-garde aesthetes alongside caftans, headdresses, turbans and tunics in an Orientalist collection. Those items deemed “traditional” and “backward” when worn on a native body were thus transformed as “fashion forward” when worn on a Western one, in what amounted to the blatantly uneven, and undeniably geopolitical, distribution of aesthetic value and modern personhood. In a Pop Matters column on bohemian fashion (or what she hilariously calls “a competition for Best Dressed Peasant”), Jane Santos details how Poiret both drew from the imperial fashion for Orientalism** as well as contributed to it:

In Raiding the Icebox, UCLA film professor Peter Wollen argues that Poiret’s designs embodied the rampant Orientalism dominating French culture at the time. Wollen describes the lavish “Thousand and Second Night” party Poiret threw to celebrate his new line. He says, “The whole party revolved around this pantomime of slavery and liberation set in a phantasmagoric fabled East.” According to Wollen, Parisian culture was in awe of the Orient, seduced by the Russian ballet’s performance of Shéhérazade and ecstatic over the publication of the new translation of The Thousand and One Nights; and Poiret’s fashions further whetted the public’s appetite for Orientalism. In addition, Poiret’s designs greatly impacted haute couture, and set the precedent for Orientalism in avant-garde fashion.

The harem, as an Orientalist fantasy of sexual excess and perversity (bearing no relation to actual practices of seclusion), depended upon imperial tropes of Muslim women’s sexuality as alternately available and licentious, or naive and repressed. In either instance, the Muslim woman was understood as a patriarchal property and an “undeveloped” personality. But as numerous feminist scholars note, Orientalist fantasies about the sexual proclivities –and possibilities– assigned to the “loose” clothing of the harem’s imagined denizens were often received as liberating for the corseted Western woman. For her, donning the harem pant (or the beaded veil or the fringed “Chinese” shawl) powerfully enacted a series of resonant fantasies about the ostensible transgression of bourgeois domestic life for a more spectacular and sensuous one, defined by shocking indulgence and theatrical intensity.

But in her essay “On Vision, Veiling, and Voyage,” about “cross-cultural dressing” by different groups of women (in this instance, European and Turkish women) at the turn of the century, Reina Lewis argues that the “thrill” of such cross-dressing for Western women was “predicated on an implicit reinvestment in the very boundaries they cross. Clothes operate as visible gatekeepers of those divisions and, even when worn against the grain, serve always to re-emphasize the existence of the dividing line.” About the European woman who indulges in sartorial tourism, “she can enjoy the pleasures of cultural transgression without having to give up the racial privilege that underpins her authority to represent her version of Oriental reality.”

TOP: LaRedoute’s much derided “harem pant.” BOTTOM: Marc Jacobs S/S 07.

What these histories might mean for the contemporary appearance of the harem pant is unpredictable. We can easily observe that we are in the midst of wars waged by competing world powers seeking to carve out influence and rule in the Middle East, and that recent runways reflect certain fears and fantasies about what this might mean.***

But there is also significant categorical confusion with regard to the harem pant, which seems to have become a catch-all term for almost any pant that is loose around the crotch, with seemingly endless variations on the amount of fabric swathing the hips and thighs, as well as the cut and cuff of the leg. Some look like jersey jodhpurs, others like roomier yoga or sweatpants (which often already come with elastic at the ankle). Still others are likened to MC Hammer’s infamously billowy parachute pants. There is no clear referent, no one “authentic” garment, to which the harem pant necessarily gestures.

It seems these garments are tied to one another less through form or fabric and instead through a concept, but the content of this concept seems confused and incoherent. Runway shows or magazine editorials might still pair the harem pant with other Orientalist signifiers conjuring an exotic sensuality or imperial aesthetic (with a pair of leather lace-up sandal wedges dubbed “Mecca,” for example, from Diane von Furstenberg), but this semiotic coherence is often (but not always!) absent from other iterations of this pant form. For example, consider that there doesn’t seem to be much reference to sexual transgression with this loose fit. In fact, the contemporary harem pant seems to be read as supremely unerotic, prompting fashion blogger Footpath Zeitgeist to wonder if the contemporary harem pant deliberately refuses overt sexuality or sexual availability.

This begs the question: Why call it a harem pant? Why not simply call them drop-crotch or low-crotch trousers, which is both more descriptive and much less vexed? Even though retailers high and low are in this game, is there still something specific about the qualifier harem that signals an avant-garde or nonconformist fashion sensibility? Perhaps the dividing line Reina Lewis discusses is a mutable one — it shifts to accommodate transformation and change, but continues to distinguish hierarchies of status and position. Maybe, the harem pant continues to conjure an artistic or cerebral aesthetic against a sartorial norm that decries this silhouette as “weird” and “ugly.” That is, the harem pant references not the exoticism of the Muslim woman, but the non-Muslim woman “brave” or “daring” enough to wear them. Such that even in the near absence of an overt Orientalism, we might still detect a subtle reiteration of its “worldliness,” a cosmopolitan self-image of adventuresome aesthetes, in the enduring usage of harem to qualify this pant. (This aura is again available only to those who are not, say, Turkish peasant women wearing the shalvar to clean the house or work the field). If so, we might do well to remember that the originality of the avant-garde, as art critic Rosalind Krauss observes, is itself a modernist myth.

Here are just a few of the discussions I found about the “harem pant” in a brief Google search. Some time when I’m not supposed to be finishing my other book manuscript, I may attempt a more coherent critique.

In a long and detailed entry called Orientalism, Culture, and Appropriation, Part 3, Farah at Nuseiba calls the Western fascination with the harem pant a form of ethnomasquerade, writing, “It is through ethnomasquerade that mass culture simultaneously exercises and hides its hegemony over the colonised Other.”

An “old school Hejabi” contemplates the laughter of her “Turkish sisters” as a peasant pant sweeps the Western fashion landscape, posting some images of the shalvar (related versions, and terms, include the salwar and sherwal) as worn by conservative Turkish women for house cleaning or field work and detailing her own adventure in purchasing a pair from H&M.

In fact, a number of the hijabi style blogs find that the newest rage for the harem pant means more options in shopping for “modest” items from mainstream stores like LaRedoute, Urban Outfitters and Forever 21. This transforms the terrain for comprehending the harem pant in the contemporary present. Even while some Muslim women might observe hijab more casually (and often defiantly) in skinny jeans and tight manteaus (and some observe not at all), others are glad for an accessible fashionable alternative that allows for looser definition. Hijabulous, for instance, cracks a playful Aladdin joke before adding, “Hey, I rocked ’em last eid and they were super comfy!” Trendy Hijab Fashionista puts together some outfit collages with these new offerings on the non-Muslim market. Still more others decry them as resembling “an adult diaper” (probably the most common denunciation of these pants).

“When a hijab-friendly trend does come along, I stock up in case it doesn’t stick around,” writes Jana Kossaibati, a Muslim woman who takes the Guardian reader on a tour as she shops the mainstream stores for long tunics and harem pants (verdict: comfortable, but not as cute on short people).

And finally, Diwan (“Your Gateway to Middle East Chic”) opens their review of the recent London and New York Fashion Weeks with a throw-away Edward Said citation and interviews Deena Aljuhani Abdulaziz, “one of the few Middle Eastern voices to be heard on fashion’s front lines,” about how a Middle Eastern buyer (such as herself) might interpret the harem pant for the region’s cosmopolitan elite.

* As should the proliferation of YouTube instructional videos on creating what is baldly called “the Arabic eye,” in conjunction with sartorial fascination and social fear about the hijabi, the veiled woman, and all the likely Orientalist connotations of an exotic, because “forbidden,” female sexuality.

** Edward Said famously argued that far from simply reflecting what the countries of the “East” were actually like, the “Orient” was created in the European imaginary as its opposite. As an array of images, ideas, and practices, Orientalism thus produces, through different forms of representation (for instance, scholarship, literature, and painting), forms of racialized knowledge of the Other that are deeply implicated in operations of power (e.g., imperialism).

*** For instance, Ellen McLarney charts the burqa’s post-9/11 evolution from”shock to chic” in her essay, “The Burqa in Vogue: Fashioning Afghanistan” in The Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Winter 2009).