In case you missed it, I have an article in The Atlantic on the limits of the usual cultural appropriation/cultural appreciation debate. I suggest, instead, that “inappropriate” conversations about fashion – with a focus on what gets left out of processes of appropriation and what isn’t appropriate-able – provides a useful way out of the back-and-forth, we said-they said discursive cycle that hasn’t gotten us very far.

In case you missed it, I have an article in The Atlantic on the limits of the usual cultural appropriation/cultural appreciation debate. I suggest, instead, that “inappropriate” conversations about fashion – with a focus on what gets left out of processes of appropriation and what isn’t appropriate-able – provides a useful way out of the back-and-forth, we said-they said discursive cycle that hasn’t gotten us very far.

ICYMI: A Case for Inappropriate Conversations About Fashion

Comments Off on ICYMI: A Case for Inappropriate Conversations About Fashion

Filed under FASHIONING RACE, THEORY TO THINK WITH

“Asian Americans in Fashion” on CUNY TV

Below is a video of a program called “Asian American Life” that aired on CUNY TV on October 10, 2013. I appear in clips about the work of fashion blogging. While the show just aired, my bit was recorded in June after a panel discussion Mimi and I were a part of about race, fashion, and economies at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA).

Filed under FASHION 2.0, FASHIONING RACE, LABOR AND THE CREATIVE ECONOMY

Why Fashion Should Stop Trying to be Diverse

UPDATE: This post is now re-published at Salon (in slightly abridged form)!

OK, I take it back. For the last six years or so, I’ve written countless articles, essays, and blog posts criticizing the lack of racial and size diversity on fashion runways and in print editorials. I’ve argued for the need to expand the industry’s vision for the types of bodies that could represent what is beautiful and fashionable so that the torrent of images that permeate the everyday lives of so many different women and girls might reflect the broad range of body types and sizes of the industry’s target and accidental audiences. But never mind. I take it back. Fashion should stop trying to be inclusive. Stop trying to be diverse.

Recent efforts to diversify fashion runways and editorials have made me both sigh and groan. I sighed when I read the letter written by the Diversity Coalition (an organization formed by Black American and British models Bethann Hardison, Naomi Campbell, and Iman) calling out the fashion powers-that-be for their inattention and inaction when it comes to racial diversity in modeling. Their letter effectively sets Asian models apart from other models of color. Apparently, Asian models don’t count as racial diversity. The notion that Asians are not real people of color or are “honorary whites” serves racism by denying anti-Asian racism—which has a long and enduring history in fashion. It also advances a deep-seated divide-and-conquer approach to race relations that ignores the way racism impacts all racialized people.

Believing the hype that Asian models are untouched by the fashion industry’s systemic racism requires that we ignore the reality of their under representation. Jezebel’s survey of nine New York Fashion Week seasons between 2008 and 2013 shows that Asian models never comprise more than 10 percent of turns on the runway. In five of the nine seasons, Asian models have less representation than Black models. And in the four seasons in which there are more Asian models represented, the difference is minimal—falling somewhere between .5 percent and 3.1 percent. This month, during NYFW Spring 2014, Asian models outnumbered Black models by the very slimmest of margins, .02 percent. By no stretch of the imagination can we take these numbers to be evidence that Asian models somehow have it easier in the fashion industry than other nonwhite models. Across these ten seasons, white models never make up less than 79.4 percent. This massive disparity can only be the result of the fashion industry’s systemic racism that inordinately benefits white models and disadvantages all nonwhite models. While I applaud the Diversity Coalition’s mission and efforts, I’m holding out hope that it doesn’t reproduce the same kinds of racial exclusions it intends to critique.

As an example of the groan-inducing moment in recent fashion history, I turn to the buzziest show of the season: Rick Owens’ show in Paris in which he used teams of mostly African American step dancers to introduce his Spring 2014 ready-to-wear line. The fashion media—so far—has universally praised the show as a “powerful” move by a leading fashion designer to overturn the industry’s dominant racial order. But “power” is exactly what’s missing in this show—and, for that matter, what is missing in the discussions about this show and about racial diversity in fashion in general. To pass muster as real change would require the racial dynamics of power that structure fashion’s visual cultures and practices be disassembled. Instead, Owens’ show represents a continuation of the same hierarchies of race and power that make it possible for a famous white designer to request that predominantly young Black women serve up “a routine that embodie[s] viciousness” for a mostly white audience.

Fashion’s racial problem is not that white models far outnumber nonwhite models on the runways and in mainstream fashion magazines. The racial makeup of fashion’s visual cultures is only a symptom of a much deeper problem: the almost-exclusive control of white perspectives to define what is beautiful. The exercise of this control is apparent even in fashion imagery and events that include a majority number of people of color if they are there to serve a racial function. Some of the most common racial functions in fashion are:

- people of color used as multicultural scenery, there to provide contrast and intensify the difference between them and the white model(s)

- people of color used as multicultural window dressing, there to cover over the reality of fashion’s systemic racism

- people of color used as multicultural spectacle for an audience of cultural tourists (who do not belong to or associate with the people whose racially gendered bodies are on display)

- people of color used as embodied evidence of the “multicultural cool” of the white designer, white brand, white magazine, etc.

What each of these categories share, and what links them as liberal multiculturalist posturing (as opposed to radically substantive change) is that each of these multicultural moments unfolds and emanates from the privileged and controlling perspective of whiteness. In these situations, the standards of beauty—as well as the standards of unconventional beauty—are established and contained by white perspectives and white needs for racial difference. Owens has said that he chose to introduce his spring 2014 line through step because he was “attracted to how gritty it was.” In the context of racial spectacles, what is important is not the cultural history or cultural present of the cultural practice on display; what is important is the display of racial difference itself. The significance of racial difference for its own sake (rather than for the sake of social and cultural political equity) is summed up in Suzy Menkes’ review for the New York Times in which she describes “the joy of seeing a sea of black faces”.

Owens’ show and the popular discussions about it are reflective of a general misunderstanding about the ways that racism and exploitation work.

As I wrote in another post, racism is not about individual intention. Well-intentioned people speak and act in ways that reinforce racism all the time. The only way to undo racism is to fundamentally alter the structures that enable whites to benefit from racism and people of color to be exploited by it.

And just as racism doesn’t require intention, exploitation doesn’t demand dominance. It is entirely possible for fun and gratifying experiences to be exploitative. (For more on this, see Mark Andrejevic’s excellent essay, “Estranged Free Labor.”) The dancers surely enjoyed the global spotlight, the free trip to Paris, and the free designer clothes that I imagine Owens allowed them to keep as a gift and because these outfits were individually tailored for each dancer’s body. Stepper Adrianna Cornish tells reporters that the experience is “something [she] never would have dreamed of”. A blogger for the Wall Street Journal notes that “some guests dabbed tears during the show” and that dancers themselves were “wiping tears” from their cheeks following the performance. To draw attention to the exploitative conditions of the performance is not to deny or diminish the fact that the show was emotionally moving for some of its participants and observers. But if racism is not necessarily a product of personal feelings and intentions then anti-racism cannot be achieved at the level of personal feelings either.

So how do we know racism or exploitation when we see it? (Hint: they are usually conjoined.) A quick and handy litmus test is one in which the following two questions are answered positively. Does one party benefit, not just more but disproportionately more, from the multicultural event than the other participating party? Does this relation of benefits mirror and repeat the prevailing social relations that already structure dominant society? If the answer to both questions is “yes” then it is a pretty good bet that the multicultural event is racially exploitative.

In the example of Owens’ show, the white American designer stands to reap immeasurable social, cultural, and financial rewards for this show. Already, the show is securing his reputation as a cultural provocateur and a fashion rule-breaker. In the professional and user-generated press, Owens is regarded as a leading force in the industry, an edgy designer, and an innovative showman. The dancers, on the other hand, are merely looked at as evidence of Owens’ creative genius, as the current hot topic in fashion (one that will, as all hot topics do, fade out), and an outré spectacle. New York magazine’s fashion blog The Cut likens them to a UFO sighting and fashion blog The Gloss describes the dancers as an Orange is the New Black celebration, referencing the new Netflix original series about women inmates. (Remember, all of these dancers are college students or college graduates.)

Thanks to the deluge of reviews, of Instagram photos and videos, and tweets, Owens’ brand is winning in the attention economy that now drives fashion in the age of social consumerism. And if others felt the way a Dazed Digital reporter did after the show—wanting “to clear [her] savings [and] buy a Rick Owens leather jacket”—then this publicity will also generate sales.

The dancers, on the other hand, the women whose bodies, energy, and time made the show will be remembered only as Owens’ dancers. The few dancers that have been interviewed and named will be forgotten but Owens’ bold statement, his powerful message, and his creative vision will be memorialized in fashion history. In academic language, Owens will be remembered as the agent of the show while the dancers will be remembered as the people who instrumentalized his agency, his vision, and his mission.

So I repeat: the global fashion industry should stop trying to be inclusive, stop trying to be diverse. Rather than count racial bodies, it should begin recalibrating its structural dynamics of race, power, and profit so that a statement like Menkes’ that “the imagination of the [white male] designer is the greatest achievement of the show”—a show brought to life by the talents and hard work of mostly Black women dancers—is simply unthinkable.

The Techno-Orientalist, White Feminist History of “Harem Pants”

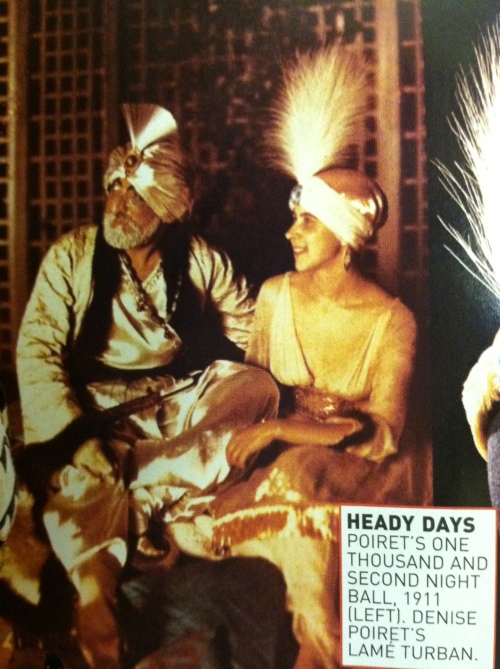

Before there was Jean Paul Gaultier’s kimono bikinis and Tom Ford’s Gucci line of satin jackets with the cherry blossom embroidery, there was Paul Poiret’s jupes sultan or harem pants. In an article that is now published in Configurations, I locate Poiret’s harem pants and his larger 1911 fashion line at the intersection of modern white feminism, Orientalism, and the Machine Age. Analyzing the design and construction of key pieces in the collection, I show how his harem pants, Mandchou tunics, and hobble skirts are a kind of “machine art” and an early example of wearable virtual technology.

While the loose design of these garments freed European white women from crinolines and corsets and enabled proto-feminist physical and social mobilities, they were also technologies of racial virtuality. Vogue and other women’s and fashion magazines at the time breathlessly described Poiret’s collection as “modern magic”. Wearing his clothes, the magazines promised, would transport the woman from “the dull materialism of the temperate zone to . . . warmth, colour, and perfume in the tropics.” And as you can see from the photo above from an article Vogue ran a few years ago on Poiret’s influence, Poiret and his wife were all too happy to participate in virtual racial play. My article includes some amazing photographs of other pieces in the collection worn by some of the Poirets’ friends.

In some ways, this essay is a “one-off” for me. I don’t usually do this kind of historical research (though it is part of my larger interest in fashion’s virtual technologies) but once I discovered this collection and the “Thousand and Second Night” party he threw to introduce it to the fashion public, I had to write about it. Also, it was maybe the most fun research ever.

The full title of the essay is “Paul Poiret’s Magical Techno-Oriental Fashions (1911): Race, Clothing, and Virtuality in the Machine Age” and it’s in the Winter 2013 issue of Configurations: Journal of the Society for Literature, Science and the Arts 21.1. (Configurations is an academic journal that emphasizes the relationships between the arts and science and technology – very cool reading, this journal.)

Meet the Burka Avenger!

I’m so excited to have just discovered this new animated series called Burka Avenger that I want to post all the episodes – 13 so far, I think – but for now, will just post the English-language trailer. The original series is in Urdu.

I’m so excited to have just discovered this new animated series called Burka Avenger that I want to post all the episodes – 13 so far, I think – but for now, will just post the English-language trailer. The original series is in Urdu.

The Burka Avenger is “a mild-mannered teacher with secret martial arts skills who uses a flowing black burka to hide her identity as she fight local thugs seeking to shut down the girls’ school where she works.”

Explaining the reason this superhero wears a burka, creator and Pakistani pop star Aaron Haroon Rashid, says:

It’s not a sign of oppression. She is using the burka to hide her identity like other superheroes. Since she is a woman, we could have dressed her up like Catwoman or Wonder Woman, but that probably wouldn’t have worked in Pakistan.

To read more about the Burka Avenger, go here.

Filed under Uncategorized

Deja Vu

2013: From the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue

2001: From the Donna Karan Spring/Summer ad campaign

Fashion photography (and I’m using the term very loosely to include SI) is sooo innovative!

Filed under FASHIONING RACE, ON BEAUTY

What Can a Discussion About Fashion Tell Us About America’s Culture of Violence? A Lot.

Like so many others, I’ve been thinking a lot about gun control in the wake of the mass shooting in Newtown, Connecticut. Although the discourse around gun control can be sometimes mystifying, if not downright mind-numbing (teach kids to rush at shooters rather than hide; enlist a male janitor to heave a bucket at the shooter’s knees??), I’ve appreciated the many thoughtful discussions that link unthinkable violence such as that which took place at Sandy Hook Elementary School to the many acts of violence that many Americans just don’t think about, like the U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan and Yemen that have killed scores of civilians (including children) and the street shooting deaths and injuries of predominantly black and brown young people in cities like Chicago, Oakland, and Jacksonville, Florida. But what does fashion and style have to do with America’s culture of violence? A better question might be, what can a discussion about fashion and style illuminate for us about this culture of violence? A lot, it seems.

Recent reports tell us there are clear links between the “aggrieved entitlement” of white, middle-class men and mass shootings (of the 62 mass shootings in the past 30 years, 70 percent were carried out by white men). But America’s culture of violence is not limited to masculinity and as Vijay Prashad reminds, it doesn’t always take spectacular form. (Though fashion media is replete with spectacles of violence. See – trigger warning! – here and here, for a start.)

There’s another, also gendered, dimension of America’s culture of violence in which women and girls are predominantly the perpetrators and victims. The “slow violence” of body dysmorphia and eating disorders are a significant, if often invisible, part of America’s culture of violence that implicates women across generational, racial, class, and sexuality differences in uneven ways.

Rob Nixon defines “slow violence” as

violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.

Although Nixon’s discussion of slow violence focuses on environmental catastrophes like industrial pollution and the aftermath of chemical warfare, his concept can be extended to the particular relation of gender and violence that women and girls experience every day. Because girls from a very young age are conditioned to believe their identity and self-worth is tied to their appearance, to please others, and to seek out the approval of others, they are especially vulnerable to the countless verbal and nonverbal messages they receive about their never perfect bodies from family, friends, co-workers, and a wide array of media including women’s magazines, men’s magazines, fashion blogs, pro-ana websites, diet and exercise books, TV shows, and websites. The failure to fulfill all the requisites of ideal femininity triggers for many women and girls the slow violence of low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression and for some others, drug and alcohol abuse, cutting, and disordered eating behavior.

A 2008 study conducted by SELF magazine and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that 65 percent of American women between the ages of 25 and 45 have disordered eating behaviors which includes skipping meals, perpetual dieting, incessant self-weighing, smoking to lose weight, and maintaining a diet of 1000 calories per day or less. An estimated eight million Americans have been diagnosed with an eating disorder such as anorexia and bulimia. Among them, 7 million are women and girls. The slow violence of body shame begins at an alarmingly early age. Consider these statistics from the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD):

- 42 percent of girls between 1st and 3rd grade have expressed the desire to be thinner

- 47 percent of girls between 5th and 12th grade reported wanting to lose weight because of magazine pictures

- 69 percent of girls in the same age bracket reported that magazine pictures influenced their idea of a perfect body shape

- 81 percent of 10 year-olds are afraid of being fat

Formal studies like these don’t take into account the slow violence of “body-checking”—the everyday pinching, tugging, and monitoring of body fat—that so many women and girls casually perform on themselves and others everyday. For nonwhite women and girls, gender violence is often bound up with racial violence. Precious few studies include the impact of racial hierarchies and norms of beauty on women of color’s everyday body-checking. The whitewashing of eating disorders (anorexia as a white girl’s problem) also conceals the role race plays in the diffusion and development of negative body perceptions. Additionally, the slow violence of pro-ana ideologies that view rigorous dieting, exercising, and starvation not as problems but positive lifestyle choices are too infrequently discussed.

The scope and scale of body shaming clearly indicate that the fashion industry is not solely to blame for this gendered sphere of America’s culture of violence. But the fashion industry isn’t entirely off the hook either. As a purveyor of millions of globally-circulating images and words that reinforce and celebrate a body ideal that 95 percent of U.S. women cannot attain naturally, it has enormous power to impact the culture of slow violence that leads to the physical, psychological, and spiritual deaths of so many women and girls. More often, though, it normalizes impossible thinness (underweight models like Coco Rocha—a 5’10” model weighing 108 pounds—are told to lose weight and already-thin models are regularly Photoshopped to appear even more slender. Although the Council of Fashion Designers of America has come out against unhealthy modeling practices and the culture of fat shame, its policies have been weak and unenforced. The CFDA Health Initiative is a set of guidelines rather than mandates. Bans against using models under the age of sixteen have been repeatedly broken without any real consequences. As a result, adult women are tacitly told to strive for a pre-puberty body, a goal that engenders a myriad of interlinked slow violences. The fashion industry’s normalization of compulsory thinness is a huge reason why we only have estimates of eating disorders and disordered eating behavior. Shame and guilt about not meeting the standards of beauty and thinness as well as the shame from trying to attain these standards when we “should know better” has made invisible this culture of femininity and violence.

It’s not my intention to detract from the national conversation about the epidemic of school and street shootings. Instead, my hope is to expand these discussions to include other relations of gender and violence that are no less a part of America’s culture of violence.

Filed under Uncategorized

INTERVIEW: Tanisha C. Ford, Haute Couture Intellectual

Timed for the new academic year, a few weeks ago Racialicious published “Haute Couture in the ‘Ivory Tower,’” a sharp essay by Tanisha C. Ford about academic chic, whose bodies are imagined to inhabit the so-called ivory tower, and the racial and gender implications of their adornment. In response to a recent New York Times Magazine fashion spread, Ford argues that the specific sartorial and other fashions on display alongside the absence of bodies of color reinforced the image of the intellectual as elite and, well, ivory. Ford observes,

The spread presumes that when a professor walks into a classroom she is a blank slate, a model to be adorned in fine clothing and given an identity. The reality is that scholars of color, women, and other groups whose bodies are read as non-normative have never been able to check their race, gender, religion, or sexual orientation at the door. As soon as we walk onto campus, our bodies are read in a certain (often troubling) manner by our students, our colleagues, and school administrators. Our professionalism and our intellectual competence are largely judged by how we style ourselves. Therefore, we are highly aware of how we adorn our bodies. And, like our foremothers and forefathers who innovated with American “street fashions,” we, too, use our fashion sense to define ourselves, our professionalism, and our research and teaching agendas on our own terms. As a result, we are actively dismantling the so-called Ivory Tower.

Totally psyched about her essay and the amazing outfit she wore in the author photograph (those are my colors, too!), I wanted to interview Tanisha C. Ford for Threadbared. I actually met Ford in 2009 at the annual Graduate Symposium on Women’s and Gender History at the University of Illinois, where she presented an awesome paper on soul culture and gender politics in the 1963 March on Washington. Ford has since received her PhD in History from Indiana University, and spent time as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan before starting as an Assistant Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexualities Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She is currently writing a book called Liberated Threads: Black Women and the Politics of Adornment. You can follow her on Twitter at SoulistaPhd.

How did you first conceive the research questions that would fuel the shape of this project, and how these questions have evolved since that first nascent encounter with your research questions? I’m interested in this process for you!

It was my love of the music, culture, fashion, and politics of the 1960s and ‘70s that initially brought me to this project. I was particularly fascinated with soul singers like Nina Simone, Odetta, and Miriam Makeba. I admired how they performed their politics not only through their music but through their hair, dress, and stage costumes. To me, their natural hairstyles, caftans, head wraps, ornate African-inspired jewelry, and printed dresses were more than mere clothing to cover their bodies. They used such fashionable items to express their unique personas while also communicating something critical and important about race, gender, sexuality, class, and nationalist politics. My interest in these dynamic women sent me on a quest to understand how and why they adorned themselves in this way. Were they alone? If not, who were the other women who dressed similarly? What influenced their sartorial choices? I discovered that there were several books and articles on black women’s hair politics, but there was far less written on fashion and body politics, especially concerning black women. With the help of some savvy archivists and women who were willing to let me interview them, I began piecing together fragments of a vibrant and complex history of fashion and its connection to histories of oppression and human rights struggles. My research led me to destinations a far flung as Jackson, Mississippi; London; and Johannesburg. What began as a dissertation project on celebrities and pop culture has—six years later—become a book monograph in progress that focuses on grassroots cultural-political engagement and the ways in which Africana women activists have utilized fashion and beauty culture as both a political tool and a means to re-imagine and redefine black womanhood on their own terms.

What are some of your favorite examples from your book about Africana women’s uses of fashion and beauty culture as a political and imaginative landscape, and how you read their labors?

I’m having so much fun writing this book, uncovering such fascinating histories. One of my favorite examples is from a chapter on the denim-wearing women of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). When I first saw photographs of SNCC women such as Dorie and Joyce Ladner wearing denim at the March on Washington, I was stunned. Women in denim overalls seemed antithetical to everything I had learned about the civil rights movement since I was a kid. I started digging into the SNCC papers, rereading memoirs written by SNCC activists, and tracking down SNCC members for interviews. I had to know why they wore denim and why I’d only learned about the women who wore dresses, cardigans, pearls, and heels! I discovered that SNCC women adopted their denim attire for both practical and political reasons. And, their overalls and au naturel hairstyles caused quite a stir on their college campuses and among many elder activists. I have used my SNCC research to revise the cultural history of the Civil Rights and Black power movement era as well as histories of radical fashion in the late twentieth century. An article derived from this chapter,“SNCC Women, Denim, and the Politics of Dress,” will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Southern History.

How do you understand the politics of respectability that are brought to bear upon women of color in the academy, and as well strategies that women of color deploy to negotiate the institutional demand that we adhere (more than others, often) to a particular “professionalism,” and its racial and gender dimensions?

My theories about the fashion and body politics of the 1960s and ‘70s have also provided a useful framework for analyzing contemporary fashion culture. Recently, I’ve been exploring the politics of dress and adornment in my own profession—the academy. Interviews with professors of color reveal that there are similarities between the strategies of adornment SNCC women employed and those used by my colleagues. Women of color in particular use their clothing to challenge and redefine notions of “professional” attire on their own terms, incorporating suits in bright colors, stiletto heels, ornate jewelry, eclectic prints, and enviable eye makeup into their “power wardrobe.” They use faculty photos, the social/digital mediasphere, and their classrooms as sites where they can deconstruct the staid image of the white male professor with glasses and an elbow-patched blazer. The award-winning women scholars I interviewed debunk the long-held belief that “serious” academics don’t care about “trivial” things like fashion and style. I’ve written a series of pieces on this topic including “Haute Couture in the Ivory Tower,” “You Betta Werk!: Professors Talk Style Politics,” and the forthcoming “A Fashionista Asks: What To Wear On The First Day Of School.” I’m hoping to turn these pieces into a longer journal-length article.

I remember strategizing so hard for my first day as an Assistant Professor years ago; I ended up in an all-black secretary outfit. Today, for my first day of teaching I wore a short-sleeved (sleeves rolled up), white t-shirt featuring a cartoon carrying books in her arms and on her head and reading “Reading is Cool,” with a yellow pencil skirt and a metal belt with two hearts at the clasp. (My sartorial style is New Wave doyenne.) Last question then — what are you wearing on the first day of school in your new position as an Assistant Professor?

What a fun question! I’m not sure yet…but the process of figuring it out has been both fun and helpful. I just moved to a new city, so searching for cool places to shop helps me learn my way around town. I’ve been finding some great pieces that speak to my fun and flirty fashion sense. I love wearing bright colors and eclectic patterns, statement shoes, and mixing “girly” prints with menswear looks. My number one fashion rule is: there are no rules! Pretty much anything can be worn together if styled properly. For example, I recently purchased a pink blouse with cream hearts on it. I’d likely pair this shirt with a navy and cream striped Zara blazer I own. As a Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies professor, I get to mix my personal style with my professional activities in cool ways. I’m teaching an undergraduate course called “Feminisms and Fashion,” this will give me the space to have fun with my attire while using scholarship on fashion and body politics to engage with my students on salient women’s rights issues. In preparation for my big first day, I’ve been having mini fashions shows in front of my mirror. These one-woman shows allow me to fall in love with my existing wardrobe all over again, inspiring me to look at my clothes in fresh, new ways. Whatever ensemble I wear on the first day of class will be fierce and fly!

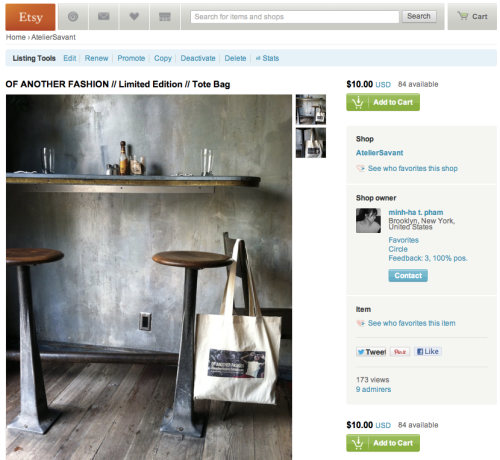

OF ANOTHER FASHION Tote Bag and Giveaway

As most of you know, I have another online project called OF ANOTHER FASHION that began several years after Threadbared launched. The crowdsourced project is doing so well (over 3oo submissions and 104,000 followers) that I decided to celebrate this milestone with a tote bag. (In some respects, I favor tote bags over traditional handbags and shoulder bags for their practicality and easy stylishness. Yes, I just wrote that: “easy stylishness”. Whatevs. You know what I mean.)

As most of you know, I have another online project called OF ANOTHER FASHION that began several years after Threadbared launched. The crowdsourced project is doing so well (over 3oo submissions and 104,000 followers) that I decided to celebrate this milestone with a tote bag. (In some respects, I favor tote bags over traditional handbags and shoulder bags for their practicality and easy stylishness. Yes, I just wrote that: “easy stylishness”. Whatevs. You know what I mean.)

To purchase a tote bag, head to my Etsy store, Atelier Savant! Thanks!

Fun fact: there was a short period of time when me and a friend – a fellow academic – considered very seriously throwing in the professorial (but not scholarly) towel and opening an online clothing store called l’Atelier Ecole. I’ve rejigged that name for my Etsy shop, kind of as an homage to this earlier imagined life. (Atelier Savant is The Scholar’s Studio, in French).

Filed under LINKAGE, OUR JUNK DRAWER