In the last few weeks, several writers have tackled the concatenation of concerns surrounding “native appropriations” in so-called hipster fashions. (Feathered headdresses, for example, are among the latest accessories for sale by retailers such as usual suspects Urban Outfitters. For not-equivalent-but-possibly-relevant commentary, see my “History and the Harem Pant,” or Minh-Ha’s “Blackface, and the Violence of Revulsion.”) Neither of us are able to comment at length right now because we’re both on our separate ways out of town (having said that, one of the first things I would do is explore the difference between an analytic of appropriation as a property relation and an analytic of alienation as a social-historical one, in response to the many comments to these posts that protest that indigenous peoples do not have a “monopoly” on feathers), but I thought I would bookmark these writers for our readers’ perusal.

Sociological Images borrows from several posts by Adrienne at Native Appropriations (a truly amazing archive) to compile a partial archive of “native style.” Lisa Wade writes,

“All of these cases romanticize Indianness, blur separate traditions (as well as the real and the fake), and some disregard Indian spirituality. They all happily forget that, before white America decided that American Indians were cool, some whites did their absolute best to kill and sequester them. And the U.S. government is still involved in oppressing these groups today.“

Julia at a l’allure garconneire penned an epic essay, called “the critical fashion lover’s (basic) guide to cultural appropriation,” in partial response to the Jezebel syndication of the above Sociological Images post. (Many Jezebel commenters expressed hostility and indifference to the post, hurling accusations of “PC policing” or suggesting that “it’s just fashion, who cares?” Julia capably responds to some of the more representative comments.)

“my favourite aspect of cultural appropriation is that it can help us begin to deconstruct our sartorial choices and acknowledges the power of clothing as a means of shaping (racial, national, sexual, gender) identity. the exact same piece of clothing can mean very different things to different people (take any politically charged piece of clothing: the hijab, high-heel shoes, doc martens, the keffiyeh, etc) and acknowledging this fact is a very important first step. the very basis of cultural appropriation gets people thinking about questions like, can one piece of clothing “belong” to one culture? what do certain pieces of clothing signify? it moves us away from basic discussions of colour palettes and cuts and styles and trends and moves us towards a more complex theorizing of fashion.”

Molly Ann Blakowski at the University of Michigan’s Arts, Ink. suggests in “The Hipster Headress: A Fashion Faux Pas” that while the trend in feathered headresses is neither ironic nor chic, it is hardly the worst injury in a long history of violence.

Not to say some people aren’t offended – it’s definitely apparent in the posts’ feedback – but I’ve got a hunch that the hundreds of years of broken promises, stolen homelands, trails of tears, and more or less genocide at assimilative boarding schools are probably a bit more offensive than lame hipsters wearing headdresses. No, it’s cool, it’s not like your ancestors killed them all or anything-” (or your university possesses their grandparents in cardboard boxes). Choosing to wear these items out to a party leaves you looking foolish, no matter your intentions. Regardless of whether or not you’re offending someone of Native origin, you’re offending yourself.

For Bitch Magazine, indigenous feminist activist Jessica Yee tackles hipsters and hippies head on:

“Whether it’s headbands, feathers, bone necklaces, mukluks, or moccasins – at least put some damn thought into WHAT you are wearing and WHERE it’s from. I know our people sell these things en masse in gift shops and trading posts, and it seems like it’s an open invitation to buy it and flaunt it, but you could at least check the label to see A. If it’s made by actual Indigenous people/communities B. What does this really mean if YOU wear it?”

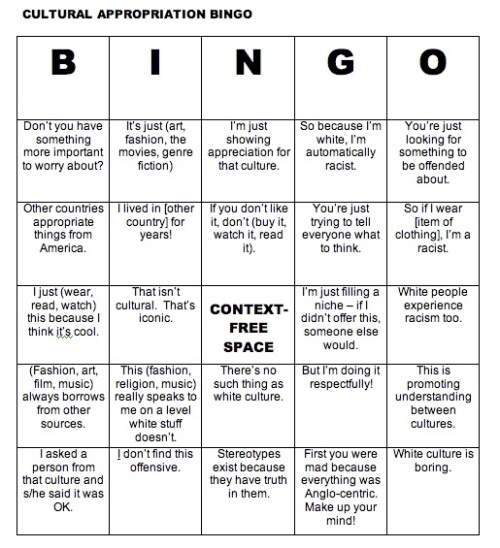

Finally, the heated comments in Yee’s post (both on the Bitch blog and on the Bitch Facebook) inspired someone to post the always-handy internet meme, the “Fill in the Blank” Bingo Card — in this case, the “Cultural Appropriation” Bingo Card (created by Elusis):

EDITED AGAIN TO ADD: Please do send additional linkages if you find them! Like this one, My Culture Is Not A Trend, which is an entire Tumblr dedicated to the apparently accelerating “feathers and fashion” phenomenon. She writes in a recent post, “When you enter into these arguments, ask yourself ‘Is my right to wear something pretty greater than someone’s right to cultural autonomy and dignity?'”

Or this one, in which K. of Side Ponytail (best blog name by the way) points to another, poignant dimension of unequal access in “on headdresses“:

April: There is a HUGE difference between being gifted authentic regalia and wearing shit because you think it’s cute. Also, a headdress is not something you wear FOR KICKS, you know?

K: I don’t know, don’t you ever have those days where you roll out of bed and say to yourself, “I deserve a headdress today!”

April: “Because in my life, every day is a pow wow! That’s how SPECIAL and UNIQUE I am!” EXTRA TRAGEDY: So many native folks, especially kids! can’t afford to create or have real regalia created. But it’s super cool that [white girls] can have [their] knockoffs.

—-

The other day April and I were talking about the recent glut of Native American “inspired” fashion trends, including (but by no means limited to) headdresses and moccasins. (This conversation was partly inspired by April’s work with an Indian community organization and my tendency to be annoyed by basically everything I see on the internet.) I thought this snippet of the conversation was worth sharing, mainly for April’s point that many native folks (especially kids, that kids part kills me) CAN’T AFFORD to have regalia of their own.

Thea Lim at Racialicious decontructs “some basic racist ideas and some rebuttals” in response to the increasingly heinous comments at Bitch for Jessica Yee’s essay.

Incidentally Bitch is also a pop culture site, so it kinda makes sense that Jessica talk about hipsters there. Bitch readers come to Bitch to talk about feminism and pop culture, but they don’t want to talk about racism and pop culture?

The “get over it” defense is not hard to take down as soon as you realise that by “it” the commenter is referring to colonisation and genocide, the legacy of which continues to beset Native communities in the form of poverty, environmental racism, and health disparities (to recap some of the things Jessica mentioned in the original post).

The whole “but that happened 100 years ago!” defense is similarly dense: a brief look at who is poor and who is marginalised in the richest countries in the world should quiet that one down…though it often doesn’t. There’s no accounting for pigheadedness.

And beyond this? Racism manifests itself in a million different ways, from massive structural inequalities, to the accessories of that fashionable person on the subway next to you. And sometimes it is easier for folks to understand and tackle the small things; for me, it was a long journey to the admission that racism exists and impacts my daily life. Talking about pop culture was a baby step that I could take; it was also something that was familiar and accessible when I didn’t really understand the academic language of postcolonial theory, or couldn’t imagine that words like “double marginalization” “diaspora” or even “immigrant” could apply to me.

EDITED ONCE AGAIN: Confused about the meaningful differences between distinct histories of exchange? They are not all the same. Read also these excerpts from Coco Fusco’s 1995 essay “Who’s Doing the Twist?” Also, new at Native Appropriations are some of the answers to the apparently compelling question, “But why can’t I wear a hipster headress?”

Because I have SOOOO much to say about this, I’m just going to say this right now – THANK YOU! Does it ever make you just want to barf that people just don’t get this?

Totally barfy!

These are the beginnings of a great and lengthy (and possibly irreconcilable) conversation. I applaud you guys.

And Natalie, I don’t think a lot of people will get it for a long time. We as a group just aren’t that mindful.

“Great and lengthy (and possibly irreconcilable) conversation” is right — if you follow up on some of the posts, particularly Jessica Yee’s at Bitch, you can really see this dynamic at work. I feel for all the commenters who have had to work so hard to counter the “it’s just feathers, lighten up!” sentiments.

There seems to be no right answer – some people are offended by someone wearing feathers whilst others don’t bat an eyelid.

I went to Glastonbury festival a few years ago and there was a Native American man with an extensive stall selling beautifully made Native jewelry, ceremonial headdresses, bone breastplates, everything you could imagine. He was selling these carefully crafted pieces to white people very happily. He certainly didn’t feel it was belittling his culture and relished speaking to my husband and I about the meaning behind each piece and how it would be worn tradionally.

I bought a beautiful silver bracelet from him and my husband bought a dreamcatcher. When I wear my bracelet I certainly don’t feel I am stealing from him or belittling his culture.

If non-Native Americans shouldn’t wear feathers, then presumably Native Americans must only stick to their traditional dress and not wear suits or jeans etc? Clearly that notion is utterly absurd.

Fashion borrows from various cultures, yes, but cultures also borrow from other cultures and have done since the beginning of time.

It’s a healthy cross pollination of different ways of life which allows different religions, cultures and races to live together and understand each other. Without it we go back the way rather than forward.

In reply to Lorraine B.

He certainly didn’t feel it was belittling his culture and relished speaking to my husband and I about the meaning behind each piece and how it would be worn tradionally.

And that’s the important part. That particular vendor gave you a great gift by telling you what where the pieces came from and their traditional uses. It was his story to tell (and sell, as it were) and not some watered down, white washed version that had no context. Think about it, yes, he was selling to a largely white audience but he was reminding them (in that oh so friendly manner) that what they held in their hands had a history and behind that history a people.

It’s a healthy cross pollination of different ways of life which allows different religions, cultures and races to live together and understand each other. Without it we go back the way rather than forward.

It hasn’t always been that healthy. Mostly it depends on who’s been able to make the most money off it.

ladyjax, it must then be asked – is it ok for me to wear feathers, beads etc that merely reference, loosely, Native culture, or “white washed” as you say, because I am now educated on the matter?

I feel very strongly that by saying no it deeply patronizes the very people it’s supposed to protect, as if they are so weak, their heritage so fragile, that they are not intelligent enough to not think of the Trail of Tears whenever they see a headdress in Urban Outfitters. Speaking to the man at the festival, he seemed more than capable of differentiating between someone like me, yes a white person, wearing a decorative beaded piece, or even a feathered hair band, and someone who is mocking his culture by wearing a fancy dress Indian costume and saying “How” at all available opportunities.

To me, there is a VAST difference between wearing that UO headdress, inspired by Natives, and wearing a genuine ceremonial headdress.

The fact is, the man at the stall was making money off his culture, no matter how you dress it up.

lorraine, as a woodland native, let me just say that seeing white folk walk around in headdresses and moccasins and various beaded items does not offend me. it is the attitude and the actions of the wearer which offends me. for the most part, those who have little touches here and there of a beaded bracelet or earings, or even the occasional small feather in your hair are perfectly fine… but when you get into the big stuff like actually wearing big giant headdresses which we don’t even wear except for ceremonies, and then get upset that we are upset, that is what i find offensive. because, quite frankly, what sane person goes around wearing something like that if they aren’t trying to be funny? and then you become angry because we don’t get or appreciate the jab at our culture. it is not up to any one individual or group to tell what anyone else what they can and cannot be offended by, and it sure as heck isn’t cool to make a joke out of anybody’s culture either.

Lorraine, I’d suggest reading through the posts I’ve linked to find answers to your questions. There is plenty of discussion in those links that can help you to think through “native appropriations.”

Also, Minh-Ha and I both distinguish between “intention” and “function.” Whatever one’s intention may be, it is both shaped by and entered into a field of power and knowledge that precedes the individual. “Good intentions,” like the desire to “civilize,” certainly paved the road to all kinds of ruin and devastation in histories of colonialism and imperialism. So we would suggest that perhaps in reviewing your options for consuming or wearing whatever, you might ask of yourself, but also of the man who “sells” his culture: What are the conditions of possibility that bring you but also him to this moment? And what place do you want to claim in that field of power and knowledge that put him in that position, and you in yours?

Great answer mimi thi nguyen!

BINGO!

Wearing feathers has a CULTURAL significance that goes beyond merely wearing clothing. Not everyone who belongs to a Native culture has the right to wear feathers, so your argument does not hold. That combined with the often thoughtless attempts at imitating Hollywood Indian culture really cross the line of appropriateness.

What people think of a redneck culture is also stolen from the Indigenous. Mullet’s anyone?

The following is a succinct summary and response to many of the comments that flew fast and furious on the Jezebel thread. The author is the poster choppery (sorry I can’t figure out how to link directly to this comment, but it’s close to the top):

Whenever there’s a post suggesting that people who don’t belong to an oppressed group shouldn’t do X, immediately there’s a flood of responses either indignantly saying, “But I should have the right!”, or scuffing their feet on the floor and muttering “Well, I’m just not sure it’s such a big deal.” Fuck that. It’s not your call to make. Sorry that the mere suggestion that someone might infringe on your privilege to “play Indian” is so off-putting to you. And it’s remarkably akin to how people defend racist jokes – because there are worse things one can possibly do, and because their effects feel intangible, they get a pass. Nevermind that withholding a joke – or ditching the “Native-inspired” garb – won’t set you back any.

I mean, let’s run through this:

“I want to wear an ‘Aztec’ patterned feather headband. But my ancestors didn’t personally oppress Native Americans. What’s the problem?”

Centuries of Native Americans – as well as indigenous peoples all over the world – have suffered under dominating entities that tried to extinguish them – both physically (i.e., genocide) and culturally (i.e., the banning of traditional practices, such as the criminalization of the Lakota sun dance for most of the 20th century, residential schools in Canada until the 1970s, and so forth).

So while it’s great that you can walk around feeling like hot shit in your feathered headband, there are many Native Americans still too ashamed or afraid to even discuss their ethnicities or cultures with their children. Many whose songs, languages, ceremonies and skills have been lost by force. Many who are so mired in poverty and depression and addiction and other forms of social strife that *you might have more access to their traditional cultures than they do*.

I’m not going to say that wearing something “inspired” by someone’s perceptions of Native American cultures is immediately and unequivocally wrong, but please consider that it has the potential to be an act of tremendous insensitivity and privilege.

“Fashion is about fun, about pretending to be someone else. Fashion appropriates other cultures all the time. Sure, it’s a stereotype, but what’s wrong with that?”

First, sometimes one person’s “fun” isn’t everyone’s idea of a good time. For example, the “fun-ness” of fashion is often lost on foxes. It’s rather like how jokes are “about fun” but can sometimes be at the expense of a vulnerable or stigmatized social group. Secondly, just because the fashion industry does something regularly doesn’t mean it’s right (I can’t believe I’m even typing this). And if fashion needs cultural appropriation to stay interesting, then axe the designers.

Thirdly, there’s a great difference between dressing up as a “stereotypical wizard” and “stereotypical Native American”. Because I fear that the distinction has been lost on a few folks, let me clarify: wizards aren’t real.

Dressing up as “a Native American” furthers the already popular notion that they aren’t real, diverse, complex human beings. There’s a reason that dressing up as a white guy isn’t nearly as effective on Halloween; there’s no homogenous vision of what White Guy looks like. If you’ve developed a homogenous vision of a particular race, enough that you could conceive of a good costume, then just fucking stay home for the evening.

It’s as though the national imagination can concoct either an “indian” regally scalping a cowboy while expertly soothing a notoriously angsty horse, or an alcoholic guy reaping welfare checks and/or the rewards of a reserve casino, and not a fucking thing in between. It might not be the biggest problem facing Native Americans (see next) but must you contribute to it?

“Isn’t this a lesser issue in Native American communities than, say, social and economic strife?”

Different Native Americans – like other types of humans, unsurprisingly – have different reactions to critiques of cultural appropriation. Some feel it’s earning a disproportionate amount of attention (and I’m inclined to agree) – just as some queer activists wish everyone focused more on suicide rates than gay marriage, and some feminists wish everyone focused more on sexual violence than the implications of Disney princesses or Barbie dolls. That doesn’t mean these conversations aren’t valid or significant in their own respect, but it does indicate that there are gaping holes in the public understanding of Native American struggles. We need fuckloads – really, I don’t know any other unit of measurement that would apply – of awareness and action about these issues as well.

To quote the amazing indigenous feminist Jessica Yee, “I’ve also heard a lot of people in the Native community ask why these types of things are getting so much attention when we have real live issues within the community like no running water and extreme poverty going on that people aren’t paying half as much attention to. But when millions of people are watching a supposed “reference” to your culture/ethnicity/race that is totally wrong – there is a bit of erasure of our people to address…”

“I think it’s okay to wear Native-themed garments or accessories as long as you’re respectful about it.”

Respect in this context is great because you can say that you have it without actually taking any concrete action. It’s like, sure, I respect you, but I’m not going lend a hand in your political or social struggles, I’m not going to write to my political representatives or join your protests or support you in any tangible way, I’m just going to learn about your people from books and pat myself on the back. Well, frankly, if your respect were a wedding gift I think most people would return it. Respect is not something you can do by lovingly reflecting on your pair of earrings, it requires a fundamental commitment of equality in your relationship with folks in your community, whether that community is your block or your planet. If you do a Wiki or Google search for “Guswhenta”, you can read about a Haudenosaunee representation of this relationship.

“But what if a Native American made the accessory/garment and sold it to me?”

There’s a difference between handicrafts and regalia. And there’s a difference between regalia and shit you think is regalia. And there’s a difference between supporting Native American trade and buying into the commodification and trendifying of someone’s culture by buying some glorious sweatshop-produced “tribal-style” moccasins at the local mall. If you can’t tell the difference and a Native American vendor hasn’t made the decision easy for you, then make the right choice. Which may not be the most fashionable one.

Well damn! Choppery gets soooo much of my friggin love for that.

-Ani8

Thanks for putting all these excerpts together in a single post – this is definitely going in my bookmarks 🙂

Just to clarify something that is sad but true – the Cultural Appropriation Bingo card created by Elusis (http://elusis.livejournal.com/1869260.html) was not created in response to Jessica’s Bitch post. You’d think so because the bingo squares are almost word for word the responses she got…but that card was actually created over a year ago.

Yes, responses to cultural appropriation critiques are that predictable! Depressing, but at least it makes a fun game…

Thanks for the heads up on the original author, Thea!

This comment is by no means insightful or astute, nor does it add anything of critical value to the discussion, but I must say: I LOVE THREADBARED (and choppery is one bad-ass articulator.) Maybe my raging love for this post is also a little bit fueled by a hipster party last night where I witnesssed one too many: white guy dreadlocks, feather headdresses, and uh, ironic consumption of hip hop music.

Jenny

Pingback: oh, BitchBlog: part 2. | Order of the Gash

Pingback: cultural appropriation link round-up. | gender, rants, and sodomy.

Pingback: Feather in Your “Native” Cap, Redux (in the time of SB1070) « threadbared

Though moccasins and the like have been enjoying a moment of popularity lately, it interests me that I haven’t seen similar discourse revolving around dress from other countries/cultures. I’m thinking specifically of imagery/garments/textiles borrowed from Asia. What about all that yoga wear featuring images of Ganesh? The skirt I saw yesterday made from snippets of vintage kimono fabric? Is it because the issues relating to Native American identity are so loaded and complicated for people in the United States?

Also, how do the Mardi Gras Indians (admittedly a very localized and specific manifestation of cultural appropriation) complicate things? I don’t know very much about their past or present, but I think their existence adds an interesting angle to this debate.

Pingback: 312. Two things: Mini for Many mini dress & untamed, unorganized thoughts on negativity, hateful things, and trying not to excuse myself or be my own hagiographer « Fashion for Writers

Pingback: Daily Outfit 4/29/10 : Wicked Whimsy

Pingback: The Wholestyle Network » Blog Archive » Wholestyle Exclusive: About That Appropriation Thing

Pingback: About That “Cultural Appropriation” Thing… | Bonne Vie

Pingback: More Native Appropriations, Heritage Capitalism, and Fashion on Antiques Roadshow « threadbared

I found your website through Racialicious, and am really excited about this site’s content, as I am also interested in questions of cultural appropriation. I have read this discussion and am also reading the links provided in this article, and as a Chicana I understand that there are problems of cultural appropriation and inequalities of power going on in these fashion examples. I am telling you this because I don’t mean to sound obnoxious, my sincere question to everyone is: can wearing a moccasin ever be okay? I understand that a war bonnet is religious and holds special meaning, but as a practical and comfortable shoe, is a moccasin always appropriation? Can a moccasin become incorporated into the dominant culture as just another shoe, or will it always be an inappropriate cultural appropriation when worn by a non-Native American?

I am trying to rack my brain for an analogy, and can’t really come up with a comparable one, but for the sake of trying to clarify what I am trying to ask–for example, you have African Americans creating blues music. Blues music has also been appropriated, but it is forever associated with African American culture and is probably identified as such throughout the world. And musicians besides African Americans play the blues and the blues have evolved and no one can deny where and from who the blues originates, and it is its own genre of music. Can the moccasin ever be just another type of shoe with its own historical/cultural background, or is my analogy completely off?

Pingback: Need « Puppenhaus

it’s like taking the guitar and style away from a blues player in the early 1900’s, and writing your own lyrics about drinking tea on the veranda of the plantation.

I’m really interested in what Amanda said. I think that moccasins can be worn by anyone. It’s true, the moccasin is definitely very comfortable and smart footwear, very durable and on top of that a pretty unbeatable pattern.

I bought a pair made in China and was promptly made fun of by my smart friend. I won’t wear them anymore because they broke within a couple days but realized that I can one day wear them without being offensive.

If I need meat for winter I can hunt an animal, cure the skins and make them myself. The main beauty and draw of indigenous fashion is that it is all handmade and gives people the feeling of working with nature. Everything comes from the earth and the curating process is often paired with socializing, reflecting, which results in building culture up.

When consumers just “get someone else to make it” — we are showing disrespect towards the consumption, by accepting it in a cheap form and getting it the easy way. (this is kind of parellel to the whole “Yum this burger is good but I would never harm an animal” ridiculousness.)

My favorite motto is “When someone else does my dirty work, I am the dirty one”.

Tiny shoes and corsetry are obviously physically harmful but moccasins are simply smart footwear. There are similar designs from aboriginal cultures from all around the world because the idea was shared and popularized – because it is a good shoe! One of the oldest for a reason! And this should be shared – no, not with native designs on it, because that’s a cultural marking. But the actual pattern, the shape of the peices that are then sewn together- is hard to bypass when there are only so many ways one can put together a good handmade shoe using animal skins.

A great percentage of store bought fashion is so far removed from independance and creativity, and so it becomes more impossible to play any role in the relationship necessary to form ones belongings. (Where did the parts of your computer come from?)

It’s not just cultural appropriation- it comes down to being a responsible consumer, knowing where that peice of fashion or any other item came from and why. Because even if the most respected aboriginal leader gave me an amazing headdress and asked if I would please wear it for so and so reason, I know that if I wear it in the city streets no matter what culture I come from that it will be a provocation, and that I better be ready to answer questions and get weird looks.

I feel it is my right to love feathers so much and sometimes wear them in my hair, but it’s also your right to tell me that I look like an idiot and probably its where I got mites.

Not a lot of people will admit that aboriginals are still suffering. The reservations here are the saddest things in Canada, people who oppose the seal hunt are wearing leathers and feathers while forgetting that in the northern reaches of Canada, many people of our native land do not have access to clean water! Until that is fixed, we shouldn’t be trying to look like them because that’s just mean. Just like whites weren’t so open about the blues until slavery and race issues were dealt with.

I stumbled upon this through a million different links and whatnot because I was intrigued by the idea that people believe that wearing an Indian Headdress and Moccasins is a form of appropriation. While reading this I was horrified at some of the narrow mindedness of people, saying that it is unfair for people to wear a culturally important piece of clothing, and linking this back to white people and their gross violation of cultural rights. Please, if you are going to begin an argument of cultural appropriation, look at history and trends around the world, look at everything, and not just one aspect, because you will see that all fashion, in all cultural settings is some form of appropriation or another, and the Indian Headdress is just another item in a long line.

First, let’s look at Tartan: In Scottish culture, Tartan is very important, it signifies which family you are from, and what clan you belong to. It is a very personal thing that is significant to each family as it represents years of war and joy and sadness, weddings, funerals and the likes, yet it is okay for someone with no Scottish heritage to walk around the streets in a pair of Tartan pants, without so much as a thought to who they might be offending or hurting by taking such a culturally significant piece of clothing and abusing it, changing it, and not giving a damn. How is that fair? Do you believe these people should be concerned with what their clothing means? Or is it okay to oppress and appropriate something from white culture?

Now let’s look at Lolita fashion in Japan (I personally love the style and so wish to one day see a wonderful Lolita), this clothing is directly stolen and appropriated from British culture, they have, in fact, appropriate everything that goes along with the culture too: tea parties, picnics, even the moral values. Now this is a massive movement in fashion and culture, where appropriation is being supported and even pushed forth, yet I have never heard anyone complain about it, not once. Maybe this is because people don’t care if white culture is appropriated, because it is deserved, or because white culture is boring… I don’t know.

How about the Beret? People often associate it with France, but it is specific to Pyrenees, this in itself is a lack of cultural knowledge, yet it is widely supported, and I would hazard to guess that some people on here, and in other places who have a strong opinion on cultural appropriation would have worn this headgear without so much as a second thought to the significance and the cultural background. Not only that, this hat has been appropriated by the military, come on, how much worse could it get? I bet they didn’t give any thought to who they might be offending.

Let’s talk about costumes! People are saying that dressing up as an Indian for Halloween is offensive and implies that they aren’t real. How about Cowboys then? German Bar Maids? Puritans? Pirates? Gypsies? Nerds? Do all those not exist then? Do we insist they don’t exist as we dress up as them? No. Halloween has turned into a night where you can be someone else, someone interesting, adventurous, fun, it is the one night a year where you are allowed to dress how you want and get away with it. It doesn’t have to be frightening anymore…

On that note, Halloween in general! Most people who celebrate Halloween don’t even know it’s historical origin, or how it came to be, or why it is celebrated, but we still do it, and most people don’t give t any thought, they just want to have fun, and in doing that aren’t they appropriating ancient Pagan culture? Pagans who were discriminated, burned, tortured, and effectively destroyed. Oh yes, Pagan culture had all but been destroyed, and yet people don’t give a rat’s ass about it. A whole culture, eradicated, and yet people who celebrate their highly religious, meaningful holidays and rituals don’t care.

There are so many more cultures that have been ‘appropriated’ by fashion, and yet there has been much less insult, much less uproar over it. I would list everything that comes to mind, but there is just so much, that I think it would be over kill..

I can see where people are coming from when they criticise people for ‘appropriating’ culture, but everyone seems to have a fairly limited view, focusing only on the appropriation of Indian culture, even though there are a host of other cultures suffering in the same manner, and being completely ignored. It is in my opinion, that there is prejudice against white people wearing clothing from other cultures, that white people shouldn’t be allowed to explore different fashions, yet other cultures are allowed to do the same thing, without so much as a thought.

Fashion is always borrowing from everything. Nature, culture, art, anything and everything. I don’t see people complaining about Native Americans wearing ‘western’ clothing, or about people wearing Tartan, or corsets or fur, or Togas. Go ahead, complain about appropriation, insult people who wear mass produced culturally significant clothing, make people feel bad about themselves, make a joke out of those who follow fashion, but if you are, look at the whole picture, look at yourselves. Take a look in you closet and think: Where did this really come from? What is the significance of this piece of clothing? Who would have worn this type of dress before me? Do these shoes mean anything? Am I really acknowledging all of the cultures represented in my wardrobe? Or am I being blind and self-riteous?

I know that I am guilty of appropriation, hell I own Doc Martens, I also own a bag of Witch Doctor Bones, and a dream catcher, I have a Chinese bedspread, and a small Zen Garden on my desk. I have read the Bible, and the Qur’an, I have read Buddhist texts and Sun Tzu’s Art of War. I come from a multicultural background, my father is British and mother is South African, I live in Australia and I have been around the world. Everything I own, I own because I appreciate it, I love the culture behind it, I have seen the culture behind it, yet, someone who visits my home, or someone who sees me walking down the street, might think that I am a racist (according to you) even though I’m not. They might believe that I am trying to appropriate culture, and for all I know, I am, but in reality, I’m not. I am not taking something from someone without their permission, I am looking at their culture and borrowing parts of it. I am not saying: “Oh, look at this bedspread that I made, based on my own culture of Drakenism,” No! I know where it came from. I know why it’s in my home, so how is that appropriation?

However, in saying all of this, I do agree there is a large amount of racism in everything, but racism in fashion only exists because there is racism in people. If we lived in a world where there was no racism (wouldn’t that be nice) then items in fashion that, now, have racist aspects, wouldn’t be considered racist. There is a need to acknowledge the economic, social and legal gap between the hegemony and those being marginalised, but in American, Australia, South Africa, and many place around the world, there is wide spread discrepancy, not only in culture, but sexuality, religion and the like, so it is important to see that there is wide range of problems to be sorted out. Fashion, to 80% of the world is rather meaningless, it is pretty or ugly, expensive or cheap, but other than that, it is nothing else. So when attacking people for their fashion choices, it should be known that they didn’t think about what it meant when they bought it, they simply liked it, and you know what? That might be a good thing – if people like aspects of a culture, surely they’d be more willing to accept it, rather than reject it?

I know that someone is going to argue with this, and attempt to blow my ideas into a million pieces, ideally belittling me, and attempting to make me feel bad for my opinions, but I feel their needed to be someone on here to highlight the gaps and silences in this article and the discussions that followed. Cultural appropriation is something that has been happening for such a long time it isn’t even funny, and yet people deem it okay, but suddenly there is a new trend, and it is instantly evil, even though those demonising it haven’t taken a look at themselves and their own appropriations.

TL;DR:

Take a look at your own wardrobe before you criticise the new trends that are emerging in society. Question yourself before you question others, and know that there is a long history of cultural appropriation, that through your own ignorance, you have been supporting.

xx

Drake.

Drake, I’m not sure who you’re addressing, but if you look around, you’ll see that Threadbared is a research blog about the politics and histories of fashion and beauty, and much of our scholarship and training is about just those histories of often violent contact and uneven exchange –of images, bodies, and capital– between peoples and across borders, and why they matter. Our response to you would be that these histories absolutely matter as the conditions of possibility for how we, but also others, are able or not able to move through the world in the present. Not all histories of contact and exchange are the same, and we believe that the differences between them matter — What relations of power are the motor for any given history? What forms of alienation might be found in these relations, including actual death (in the indigenous case, genocide) but also social death (persons rendered alienable from rights, but also life, humanity)? What strategies of survival and critique might arise from such histories and conditions (see for instance native performance artist James Luna, who parodies histories of appropriation in museums)?

I will also cite here Coco Fusco, who writes, “What is at stake in the defensive reactions to appropriation is the call to cease fetishizing the gesture of crossing as inherently transgressive, so that we can develop a language that accounts for who is crossing, and that can analyze the significance of each act. Unless we have an interpretative vocabulary that can distinguish among the expropriative gestures of the subaltern, the coercive strategies that colonizers levy against the colonized, and dominant cultural appropriative acts of commodification of marginalized cultures, we run the perpetual risk of treating appropriation as if the act itself had some existence prior to its manifestations in a world that remains, despite globalism, the information highway, and civil rights movements, pitifully undemocratic in the distribution of cultural goods and wealth.”

Again, if you look around, you’ll see that we address a number of specific case studies as well as offer some general analyses that might answer some of your concerns. At the same time, looking around will also make clear that:

a) We often respond to something that is “happening right now,” as we did in this post, which is, after all, just a series of links to a lucky congruence of other essays that address the specific case study of the “hipster headress,” which has in recent months become “a thing.” This post was in no way intended to address all histories of contact or exchange nor all their possible appropriations and interpretations thereof. This is the beauty of the blog as writing form — it allows us to gather citations, to offer some brief thoughts, with immediate relevance, and sometimes it allows us to theorize at greater length. This was a case of the former, rather than the latter. However, if you are confused as to why this iteration of “native appropriations” is important now, and what that means about its specific histories of contact and exchange that are different from other histories of other objects, the links provided in this post can guide you to some illuminating readings.

b) That said, again I will note that we have addressed other forms and histories of racial (as well as class) masquerade in previous posts.

c) And that said, Threadbared is a research blog that is not “our jobs.” Therefore, we cannot and will not respond to every single event, however minor or major, in fashion and dress. These “absences” are part of the nature of the blog form too; as Minh-Ha has written about in this same blog, the writing we do for Threadbared is both laborious and uncompensated (even if often invigorating and fun). We cannot possibly address every single item that comes down every runway, each year, to determine its historical provenance. Nor do we want to. This doesn’t mean that we’re not bothered by, say, as you point out, the fantasies of Inuit cultures that are sometimes incorporated into collections, or that our interest isn’t piqued; it means that we address those events we have the time, or the energy, or the inclination, to do so.

Please do consider reading some of the writing at the links provided; I do believe that many if not all of your concerns are addressed in these (both in the posts and in the comments sections), as they are quite familiar ones.

Thank you for this wonderfully written post.

Before I was born, my mother and father would make regular visits to a nearby reservation to learn about that aspect of our heritage (we’re celtic/native mix, so… lots to learn about), but for some reason they stopped after I was born. I’ve been trying to learn more about it on my own. I don’t want to ever wear something, and have it turn out that it has some major cultural/religious significance. It’s the whole reason I quit wearing crucifixes. I find them pretty, but it feels wrong to wear a religious item that I don’t believe in for decoration.

When I started watching some fun cartoons, which later turned out to be Japanese animation, I figured I should learn about the culture before I got too involved in the animation/comics, and ESPECIALLY the fashion as a hobby. Again, one just doesn’t want to wear something culturally inappropriate.

I admit, I get offended when people flippantly wear native items, or make comments regarding my last name, “So, bet you drink a lot, huh?” I also, for some reason, am bothered by the ridiculousness of St. Patrick’s Day, with all the glittery green crap/green food and drinks, and the expectation that I should be into it 100x’s more than anyone else.

Pingback: Post-Halloween musings: Fashion and Cultural Identity | Listen Girlfriends!

I hope it is ok if I post these links to very short commentaries that I wrote concerning this topic.

http://www.lastrealindians.com/axCommentDetails.php?postId=2130

http://www.lastrealindians.com/axCommentDetails.php?postId=2117

Pingback: The Academic Activist | Post-Halloween musings: Fashion and Cultural Identity

Pingback: appropriation « hear the sound of the guru

Pingback: shemustchallenge

Pingback: Radical Movement: Re-framing Exercise | Beauty versus the Beast

There is no such thing as white culture anymore than there is red culture. If it’s ignorant to have a team called the Redskins it’s equally as ignorant to talk about ‘whites’. People with white skin have individual cultures, they are English, German, Spanish, Catholic, Jewish, Quaker, etc. First Nations, Native American, Indian these are all generalizations too. Every nation, every tribe has their own traditions, their own definitions of what is sacred, exactly the same as so-called whites. I wish everyone would stop making these generalizations, there isn’t agreement between reds about what is sacred to them anymore than there is agreement among whites. AIM activists protest the Atlanta Braves and Washington Redskins and the kids on many rezs are buying and wearing the jerseys. Many tribes are locked in court battles about who is even entitled to be enrolled. Quakers stopped wearing plain dress long ago but people think they still do because of the Quaker Oats logo. Cultural appropriation happens to every culture. There is no point getting offended, it’s better to look at it as a teachable moment. If someone’s attitude offends you then tell them why, there is nothing else you can do.

Pingback: Pharrell Williams wears a headdress on the cover of ELLE UK.

Well I do have a feather in my native hat – but it’s a German native hat. So I’m hoping I can get away with that!

Pingback: Glastonbury Festival: Ban the sale of Native American-style headdresses on-site from 2015 | alt.LEFT